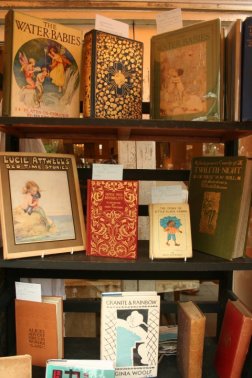

An independent bookstore in Edinburgh.

An independent bookstore in Edinburgh.

It feels like the end of an era. Another independent bookstore in Delhi recently announced the pulling down of its shutters. Fact & Fiction is the Al Pacino of Delhi bookstores, diminutive but like dynamite. Every reader in the city worth her or his salt has tasted of its offerings and emerged happier, wiser, more enchanted by literature, by life. It’s the kind of place that gives you a sense of privilege just by being privy to the knowledge that it exists, that you can spend an afternoon there. The rotating shelves near the entrance hold an enthralling promise that allows you to traverse different domains of handpicked experiences. Remember the flutter of excitement you felt while watching The Crystal Maze on TV? As you step on the ladder to reach out for a book on the upper shelves, you transcend your own worries and cross over an invisible boundary that separates the wheat from the chaff. Fact & Fiction is a world that erases lesser worlds.

Where do I begin?

In my ideal world, bookstores should stand witness to the blossoming of young love, their walls enclosing the exchange of serendipitous encounters — not a bar or coffee shop, but a bookstore. And so it did, this bookstore. It was a candyfloss of fantasies, standing out in its simple, alluring authenticity. And I lived out my own fantasy there. When I was younger, I met a girl there. I forget her name. It was a different time, a time of short hair, open sexuality, barely a care in the world. I was then managing a bookstore myself, and also had pretensions of being a writer, or wanting to be one.

I watched her as she browsed through a bunch of novels, all the time making like I was concentrating on the shelf behind her. Man, was she pretty or what. We were within touching distance, and I was pretending to be immersed in the blurb of the book I was holding, Cafe Europa by Slavenka Drakulic (again, a wonderful book that you would only come across in a bookstore like Fact & Fiction). Minutes, or aeons, passed. My mouth was dry. Then the gods smiled. She looked up at me and uttered that tome-tested line every book lover wants used on them sometime. “Have you read this book?” And conversation flowed.

She was a girl after my own heart. We spoke about the books we adored, our love for poetry, I told her about the short story I was working on, she told me about a funny incident in another bookstore. I don’t know if this is imaginative glazing but I think we talked about the meaning of life and what kept us up at night as well. “I’ve seen you before,” she said. “It’s possible. I work in a bookstore,” I replied. I invited her to the store, and promised her a cup of coffee and a discount (shouldn’t more dates be of that nature?). We arranged to meet at the store in the next few days. It was the closest I ever came asking a girl out. It was surreal. I remember walking on air as I left that hallowed space, clutching on to Cafe Europa as if my future depended on it.

Needless to say, she never came. But that’s never really the point, is it? In retrospect, it seems like all my experiences in the store that day were meant to be short-lived. Cafe Europa also remained with me for only about a month before it was lost to the wiles of irresponsible book borrowers. I looked for it in every other bookshop I subsequently went to, but in vain. That’s when I got the idea that the gentleman who ran the store was not just a bookstore owner but a curator, a gatherer of beautiful world views under one roof. Ironically, I only found the book again only when I looked it up and ordered it on Amazon last year.

No, this is not an elegy. The brilliant store owner, Ajit Singh, has written his own elegiac tribute, as have others affected by its impending demise. Yes, we all probably expected it, steeling ourselves for the inevitable. Yes, we are all culpable. Yes, I too visit bookshops with none of the intensity or frequency that I used to. I too check prices of books on Amazon.in and order from there because it’s convenient. And I regret, regret how my life has become ruled by convenience. Of course it doesn’t end there. For everything comes at a cost. So what is the cost of convenience? The erasure of a fundamental experience? Must bookstores too follow in the footsteps of the shutting down of VHS shops, of music stores, the era of cassettes, the cheap thrill of finger rewinding?

Yes, things change. My body is changing too. Pregnancy will wreak some minor havoc on my previously skinny frame, of that I have no doubt. A baby will change how I see life, and choose to lead it. And I cannot stop that, much as I want to remain my earlier self. Yes, times change. But there are some things that remain constant. My spirit, for example. Another thing that doesn’t change is how bookstores make you feel.

All my life, the one thing that has always made sense to me is books. I was a single child, often lonely. I found in books my friends, my fantasies, my weapons against a cruel world. As I grew, books grew to become my anchors of moral judgment, my guide through the grey areas of experience, my window to other cultures, my conduit to empathy, my sense of self. Books that I could hold, sleep with under my pillow, read on the pot, carry to the doctor’s waiting room, pass time on a train/ metro/ bus/ airplane; books that I could open and point to a random line which would then answer the current dilemma plaguing my life. Their very tactility, their slight weight that is the marker of a reassuring presence; the slight breeze against your cheek as you shuffle the pages.

My parents took special care to nurture my love for books. While growing up, my mother would assign me to learn new words every day from the dictionary and write them down in a special journal. Even when I began earning my own money, they always told me that one thing I had carte blanche over was book allowances from them. As long as they lived, I could always ask them to buy me books.

As an adult, I always skirted around professions that involved an intensive engagement with words, whether it was journalism, copy editing, running a bookstore, transcribing. I studied English Literature for a long time. After my Masters, I thought of moving away from that and pursued an M.Phil in Social Sciences, and now a doctorate in Law and Governance, located within the domain of political rationality. But my research interest, the history of literary censorship in India, veered back to fundamental questions around the relationship between literature and law, religion, politics, history, memory, identity. I married a man whose book collection possibly outnumbers mine (it is a sore point in our relationship). I cannot imagine being with someone who doesn’t read. Always, the magic of books has meant so much to me.

If you are no stranger to Delhi, you will remember the closure of another wonderful independent bookstore, The Bookworm, about seven years ago. If you run a Google search for Bookworm, Delhi, it will still show up: B-Block, Connaught Place. Eerie. Like coming across the Facebook profile of a dead person. The flesh and pulp is gone but the blur remains. That store which I loved and frequented (their Foucalt and Derrida were so cheap!) was the place where I first attempted to actualize my desire to work in a bookstore. I remember just having finished my Masters and being in between jobs. I was crossing The Bookworm when I saw a sign on the door. “Hiring. Manager Wanted.” I was going to go in and apply for the job. My mother was with me then, and dissuaded me saying that I could not romanticize running a bookstore to the extent that I did. It wouldn’t pay, it would be frustrating, I was just starting with my life — the standard arguments. I listened to her then.

But sometimes you just can’t be stopped. Three years later, I did actualize that dream. I helped establish a bookstore, CMYK, in Lodhi Road, and ran it as a manager just to understand the experience. I walked into a room with empty shelves, and left it a bookstore. I stacked every book, every magazine, in the niches that some occupy even now. I learnt the accounting software and inventory management, started visiting other bookstores to see what the “competition” kept, had regular conversations with book and magazine suppliers, learnt the ropes. I learnt how hectic running a store can be, and no, I never had the time to just put my feet up and browse my favourite books. I was either receiving book orders or making them, manning the till, taking stock, mingling with customers, offering suggestions when asked, or preparing for a book reading or film screening in the evening. But at some point in the day I would pause and look around that expansive space, filled with beautiful tomes on art, design, photography, travel, cookery, architecture, interiors, textiles, history, and would tell myself “This is Paradise. And You are in charge.”

I want to do it all over again. On my own terms.

And that’s why I am so worried. I am anxious about the future, about living in a world where there are no independent bookstores, where bookstore owners aren’t curators who work to stimulate the reader’s mind but algorithms that give you access to the book you are looking for. I dread the day (it’s almost here) when we will only encounter bookstore chains in malls which mainly stock penny dreadfuls, bestsellers, and self-congratulatory narratives of embracing modernity. I fear for my child, for the legacy we are going to leave behind, one of alienated experiences of reading, no visceral excitement at visiting your favourite bookstore, no exchanging knowing glances with kindred spirits, no being lost for what seems like hours in that wonderland. No playing Alice.

Earlier this year, my partner and I visited Dasa Book Cafe, Bangkok’s largest secondhand bookstore. Watching us systematically stack up a massive pile of books to buy with bemusement, the bookstore owner and his extremely genial friend got into a conversation with us. The place was full of treasures that they helped us excavate, from Anthony Burgess’ magnum opus Earthly Powers to Antoine du St. Exupery’s “Wind, Sand and Stars” (which I bought after the friend’s exposition on women’s penchant for Exupery’s prose, his wife’s love of his philosophy, and how he had bought the book for her). Both men in the prime of their lives, they had stories about George Orwell’s eccentricity, Burgess’s linguistic genius, Hunter S. Thompson’s crazy life, peppered with their own life stories, their own trysts with reading and writing, and the former’s experience of running bookstores in other countries. We stood around and chatted for an hour. We left with 15 books. Again, serendipity.

I know bookstores aren’t doing well. It’s a question of commerce, not romance. But the future is in our hands, it is something that we are partially responsible for, even as technology influences all our decisions, and always seems to be one step ahead. I want to recreate that experience for future generations. Nobody should have to live life without the pleasure of unmediated encounters with books in spaces where they are still held sacred. I wish we would all make the effort to go down to our nearest independent bookstore, buy a book, meet like-minded people, select and small though the set may be, and keep the flame alive.

An independent bookstore in Edinburgh.

An independent bookstore in Edinburgh.